7/14/10

Sculptor Sigrid Herr

In an age of mass produced, digitally rendered cemetery markers, Sigrid Herr of Art Of Remembering, creates a qualitatively different product. Collaborating closely with grieving family members, Ms. Herr creates clay models by hand. These forms are in turn cast into beautiful one-of-a-kind bronze memorial cemetery markers. Born and raised in Germany , and currently working in the San Francisco Bay

Pat McNally: You describe your start in creating grave markers to be a collaborative process with other members of your family. I’ve found that the more ways a family can participate in memorializing their loved ones, the more healing that memorial is for them. Could you describe your experience in designing your mother-in-law’s marker?

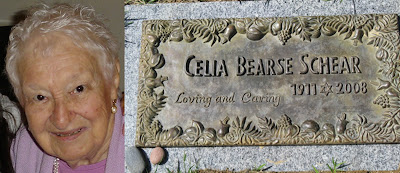

Sigrid Herr: In the Jewish tradition there is a year between putting a person in the ground and assigning a burial marker. When it came time for us to find one for Celia, my mother-in-law, we considered the options and were disenchanted by all of them: they were bland and unimaginative and felt like a bad match for the beautiful person she was. We wanted to express our gratitude for her, our appreciation, and we wanted to manifest that she was special and loved. Being a sculptor I decided to create a marker rather than buy one online or through a catalog that the funeral home provided. Celia always encouraged and supported me in my work, and owned several of my pieces, so we agreed she would have liked that. Being able to show our caring, express our connection and create a design with Celia in mind helped our family deal the sadness we felt with her death. It was like a last interaction with her, finding a way to represent her, like a portrait.

Sigrid's late mother-in-law, Celia Schear and her finished marker

When my father died last year, my mother and my sisters and I came together for his funeral. I remember my mother taking comfort in the first raw days after the death of her husband of 60 years by making plans for how she wanted their gravesite to look. It was as if it was her last act of housekeeping and presentation as a couple. In this time which often generates feelings of helplessness and having to accept a huge loss, creative efforts soothe the family left behind and provide an outlet for caring and loving feelings.

Sigrid with her father's memorial

Pat: What is the design process like to create a memorial marker for someone you have never met?

Sigrid: I often try to google the person the client calls about, so sometimes I have an idea already about who he or she was and then I can ask better questions.

In conversation, preferably in person rather than over the phone or by e-mail, I try to get a feeling for the person who will be memorialized. The friend or the relative calling usually appreciates the opportunity to talk about the person they lost. I support this by asking questions like what they loved most in the world, what made them happy, where and how they grew up, what their tastes and style were like and about their relationships. I make sure to let them know that I can appreciate the difficult challenge of accepting what they are faced with. I ask for photographs of the person the marker is for which then sit on my work table while I am working on the marker.

In conversation, preferably in person rather than over the phone or by e-mail, I try to get a feeling for the person who will be memorialized. The friend or the relative calling usually appreciates the opportunity to talk about the person they lost. I support this by asking questions like what they loved most in the world, what made them happy, where and how they grew up, what their tastes and style were like and about their relationships. I make sure to let them know that I can appreciate the difficult challenge of accepting what they are faced with. I ask for photographs of the person the marker is for which then sit on my work table while I am working on the marker.

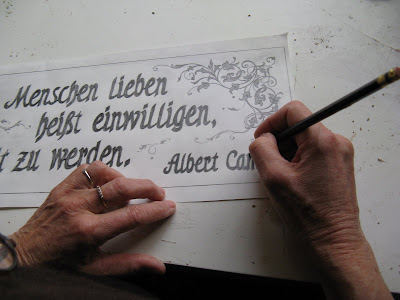

Design work

I encourage the person calling to think of symbols and designs the person liked, to get together as a family or a group of friends if possible to brainstorm and reminisce. One mother remembered her daughter’s fondness for roses, how beautiful her garden was and how much she loved her plants, and the birds that she watched out of her kitchen window. So I came up with a design that incorporated birds and roses and sent them to her.

I usually end up with a fairly distinct feeling for this person that guides me and inspires my creative proposals and decisions. My goal is to design something that the person would have liked, and something that evokes that person’s memory for the people coming to visit the grave.

I usually end up with a fairly distinct feeling for this person that guides me and inspires my creative proposals and decisions. My goal is to design something that the person would have liked, and something that evokes that person’s memory for the people coming to visit the grave.

Creating a border in clay

Pat: Many of us today look to leave a lighter footprint on the earth, with the idea of preserving its beauty and diversity for future generations. Still, our families and friends need to acknowledge that their loved one mattered and their passing matters too. How do you reconcile these two ideas?

Sigrid: I understand and admire the concept of green funerals, its lightness and its commitment to impermanence.

But the creation of bronze markers follows a long artistic and historic tradition. Today we admire and preserve bronze pieces from centuries back, parts of traditions and rituals from times long gone, witnesses that survived due to their strength and durability. When I take walks in old cemeteries, I marvel at old markers, the older they are the more amazing they are to me.

But the creation of bronze markers follows a long artistic and historic tradition. Today we admire and preserve bronze pieces from centuries back, parts of traditions and rituals from times long gone, witnesses that survived due to their strength and durability. When I take walks in old cemeteries, I marvel at old markers, the older they are the more amazing they are to me.

When talking to a friend about how I had found my way from creating figurative sculptures to the making of grave markers, I commented a bit flippantly “how un-Buddhist” my current occupation was. In Buddhism, holding on to the illusion of permanence of any kind is one of the ways we perpetuate suffering. And here I was making fancy grave markers in bronze that most likely would outlive the person commemorated by many lifetimes.

In yet another conversation, one about getting older and facing death (which with my advancing years is becoming more and more personal), my partner in conversation, familiar with my wrestling with this huge elephant-in-the-middle-of-the-room question, commented on how she couldn’t get over the fact that I was making grave markers now. As soon as she brought it up, she voiced her idea of why I was taking to the task with such passion: “You are saying: I was here and it matters. And you are telling the other person: You were here, and it matters.’’ With an instant sensation of heat in my chest and a swelling of tears my body confirmed this as true before my mind followed.

I think there is a place for both, rituals in the spirit of impermanence and rituals that serve as markers of time and history. My awareness of taking up space for centuries and for using precious resources makes it all the more important to me to create consciously and thoughtfully, to not cut corners in terms of the material and the casting process, to care about quality.

I think that beauty and art are a something to be cherished by both individuals and society. One of my goals is to make my markers accessible to people who normally would not be able to afford them. That means making a living by selling enough of them to people who have the money to commission them so I can offer discounts and pro bono work to those with fewer resources.

A marker in its clay stage

Pat: What is it like emotionally and physically to create these memorial markers?

Sigrid: Like many people, I am an obituary reader. The reason why I read the stories and study the pictures is that I feel like I honor the people who have passed away by taking the time to learn about their lives. I honor them by seeing them: you were here, this was your life, a life that spanned years and decades and that is now compressed to mostly 300 words or less. I feel compassion for them, for all that doesn’t get mentioned in the brief write-ups: hardships, growth, set-backs, disappointments, hard work, and weaknesses alongside the more pleasant and presentable facts of life like birth, marriage, children and professional achievements. I feel compassion for all of us working so hard and for mostly wanting to be good and happy. And then death approaches and leaves us with no certainties.

Clay

I am striving to embrace emotionally the Buddhist view of life and our experiences as a succession of clouds on the sky: they come and they go, and that is all and that is enough. No permanence, rather impermanence. I am in awe of this task, trying to tolerate shapelessness when all I know is shapes, creating shapes with my hands, creating shapes in my mind by trying to find explanations and making sense of what I perceive.

I hope I will be able to peacefully embrace shapelessness in this lifetime of mine. I realize how lucky I am to have found a way to work on the answer to this question that stares all of us in the face with more or less intensity at some time in our lives, not just with my mind but with my hands and with my creativity.

So I love my work, because it allows me to express my appreciation for life and for all my fellow human beings with all our frailties, shortcomings and amazing strengths by casting in bronze: Yes, you were here, and yes, it matters.

Cast in wax

Pat: You have an extensive background in sculpture. What were some of your previous projects like?

Sigrid: I initially studied art to be a teacher. I did that for a while, but felt too limited by the challenge to foster and encourage the children’s creativity on the one hand and to judge/grade their work on the other.

When my son Theo started playing with play-dough around age 2, I would work alongside him and more and more sculptures took shape. They came from a place of need that most of us have, a need for moments of sweetness and peace. The idea to sell them arose from the supportive and positive comments of my family, friends and other people who saw the figures. My sculptures all come with a story and from experiences I had. I felt them in a dream or in real life, being a mother, a lover, sitting in meditation. I also expanded to more decorative items for the home and office such as sculptural mirrors, bowls and several small and larger fountains.

Finished bronze marker

Pat: As a European, do you see differences in the ways we grieve and memorialize in North America ?

Sigrid: Growing up in a small town in Germany

My family and I went through the experience of burying a family member ourselves when my father passed away last August. There were visits to the stone mason, my mother and my sister took a trip to the quarry to select the granite onto which the bronze letters would be mounted. My mother planted flowers on the grave and makes a visit several times a week. It is a healing ritual, and in the area where I come from, it is as important as when I was a child. Overall I would say that there is more family involvement and more individualized memorialization there still. Graves look like small patches of gardens and are being tended by the people mourning. There is often ornate funerary sculpture, guardian angels or religious symbols.

Another difference is the fact that you get to own the grave for a limited amount of time only: after 25 to 30 years most graves usually are made available for new burials. This is true for German cemeteries. I don’t have information how it is regulated in other European countries.

In this country most people are no longer living close to their family burial sites. We get disconnected from the place and the ritual at life’s end.

Marker seated in granite

Pat: The biggest funeral industry catch-phrase these days is personalization. We put stickers on caskets or scan photos onto cards and gravestones. Much of the personalization is more like printing a logo onto the same t-shirt, rather than tailoring a garment to fit a specific person. What is the difference that an artist and the collaborative process can make in a memorial marker?

Sigrid: There is more humanity involved in the process, a connection is made between people, and the work reflects that. I am not saying that there is no humanity involved when you buy a marker online or through a catalogue. But it is limited. When working in close contact with the family, you can have a positive impact on the grieving process. You can engage the people in mourning in a last dialogue with their loved one through this piece of art. You can provide an opportunity for the family to express their love through their involvement in creating something beautiful and personal. Art can be soothing and a personalized memorial marker provides comfort through beauty.

Pat: Words on a monument, perhaps because of their finality and the need to be succinct, take on a lot of meaning. What advice do you give families on wording?

Sigrid: Sometimes it is harder for people who are very close to the deceased person, and very emotionally affected by their passing, to come up with a description of the person’s essence. It feels like a limitation, almost frustrating, to keep it short and succinct, three or four words. There is so much to say usually. That was the way it was in our family when my 17 year old son stepped up to the task, with the words “Loving and Caring.” Often someone with sort of a “beginner’s mind”, a child or an adolescent, or a family friend unencumbered by family dynamics, may have an easier time finding the key words. So it is worthwhile to consider if there is someone who is close but not too close to help with this task. There may be a person who knew the person in a religious or spiritual context who would be glad to be asked. Make it a conversation, use it as an opportunity to remember the person and what was special and important about him or her. Reminisce, cry, celebrate, and sooner or later the memories will get distilled into a few words that capture a person’s essence and presence and that will linger after they have passed on. You will know in your heart when you have found the right words: you feel that you have narrowed it down to what distinguished them from others and what was their life force.

A sample showing finish and border options

Pat: Have you thought about what you’d like on your own marker?

Sigrid: Yes, I have. This is a practice that can help provide guidance for your life, helping you become clear about what it is you are striving for. And it may change many times. I regard it as finding qualities to live up to, intentions that shape your actions and that describe your values. So I say with humility, knowing that I fall short daily, that the words I strive to achieve are: kindness - courage - grace. That for me would sum up a life well lived.

A sample showing finish and border options

Pat: Do you have many clients who arrange for the markers to be made prior to death?

Sigrid: I currently am working on a marker that unites seven members of a family. Only two of them, the father and the mother, have died. The other ones are their sons and daughters and their partners who are well into their fifties and sixties. The daughter was the person who contacted me. She had read about my work and was relieved to have found someone to help her realize her dream: to bring her family together, to have a home waiting for all of them at their lives’ end. She was very moved and happy to have found someone to help her make it happen. When you work with one of the big manufacturers, there are limits to what you can do. When you have only dates of birth and not the dates of death to work with, the dates of death will be added on later, etched on a small plaque and screwed on top of the marker. That always looked awkward to me and I figured out a way to make it look integrated and organic: the dates of birth will be part of the plaque, and the dates of death will be added when these times come. They will look identical to the first dates and will be added with the help of a set of numbers that I prepare and that can be used by someone else should I not be there to conclude the work. Such details are important to me and they require creative solutions.

A sample showing finish and border options

Pat: In the Bay area where you live and work there is the precedent of San Francisco San Francisco San Francisco

Sigrid: Until I started this work I wasn’t even aware of the fact that there are no cemeteries in San Francisco

A sample showing finish and border options

The same perception applies to creating a cemetery-free city zone with the argument that a burial ground would be wasting precious real estate. Yes, cemeteries take up space. But they also are part of the life of a city, town or village. Banning reminders of death beyond city limits so we can build more condos for the living. So we are not reminded of death.

I believe that cemeteries hold an important space among the living. They serve as reminders of what will happen to all of us. They provide comfort for those grieving. My mother visits my father’s grave several times a week. She visits with him and communicates with him there. It is important to have a place to visit. We are object-oriented people and people who assign spaces to experiences. By removing burial sites out of our daily lives we take away a reminder of our mortality. Only to be shocked into reality when it happens to someone close.

Pat: What can consumers and funeral service providers do to give the arts a greater role in memorialization?

Sigrid: There are consumers who are looking for artistic and unique ways to honor their loved ones. They simply need to be offered more artistic options when deciding on their memorials. My experience is that they will gladly participate.

Pat: I hope that funeral directors find more creative ways to work along with artists, celebrants and others so that families can truly benefit from all that is available for them. Thank you so much for sharing your experiences and thoughts with us! To learn more about Sigrid Herr's work, visit her Art of Remembering website, her sculpture website a recent article in the Contra Costa Times, and an article on her work in the SF Gate.

4 comments:

This is such an interesting and rewarding interview, Patrick,thanks. And it is so because of the good lady concerned, and because you ask such careful, productive questions. The potential tension between her Buddhist belief and the function of her art form is fascinating, as is that between the carbon footprint of what she does and the global warming fears we have. Her decription of heat in her chest and tears in her eyes even before her rational self knew her view was the right one is so clear. It also endorses the view of Damasio that emotions (as opposed to feelings) are generated by bodily processes and reactions before we rationalise them.

Spellbinding reading -- nothing less. "We are an object-centred people" she says somewhere (I hope I got that right). Quite so. And there's all the difference in the world between materialism and refusal to let go, and the creation of a beautiful object which can talk in so many ways.

These markers are absolutely stunning! They are truly works of art. I think they are something that could be featured on my business partners website, www.funeralresources.com. Contact us, if you're interested!

Have a great day!

A friend just send me this blog and it is very interesting. Maybe you could create for us as well. Ich bin auch Deutsch. Meine website ist www.Memorials.com

Post a Comment