March 25, 2009

Andy Warhol's 'Undertaker'

Mr. Warhol's work has certainly appreciated in value since his death

We are all familiar with the idea that artists such as writers, painters and composers only get their due once they've passed on. True or not, this is a familiar theme in our culture.

Perhaps it gives struggling artists some comfort to think of all the throngs of admirers praising their work and immortalizing their name at some point in the future.

For if the truly great are never really appreciated in life, that must be proof of just how great we are when no one sees any value in our work today. "Laugh if you must, and send me letter after letter of rejection, but you'll miss me when I'm gone!"

The idea does seem plausible. After an artist has died, the supply of their work becomes fixed, or shrinks, while the demand could conceivably increase as the world finally catches up with it's pioneers and visionaries. We can all name artists whose stature in the arts has grown as their physical remains diminish; Beethoven, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Sid Vicious, Arthur Rimbaud...

Jean-Michel Basquiat Untitled (Skull) 1982

But is there really a post mortem bump? A death effect on the value of art? If so, does it last, and does an artist who dies unknown have much of a chance at fame after death?

My uncle ran a used bookstore, The Antiquarium, in Omaha, Nebraska, for many years, and I remember overhearing call after call from folks who assumed that the old book they found in their attic was valuable simply because of its age. Not so, my uncle would tell them. Unless there is a demand for the work of the author, it's just an old book. The store was comprised of many floors, filled with books, and I had never heard of many of the authors. I suspect that no one else will hear of many of them either, and these are people who were actually published.

Cleary we do not all have a good chance at being a household name, and while Warhol's tired old saw about the 15 minutes of fame becomes more plausible every new TV season, I don't think I'll remember Omarosa or Jade Goody ten years from now.

But enough of the anecdotal, how about some cold hard research?

In a study published on ArtEconomics.com, Researchers tracked 560 painters, collecting information on nearly 266,000 auction sales in the years 1959-2003. They found the existence of only a temporary "death effect". The effect was further limited to “star painters”. The market value of lesser known, or “average painters” did not increase as a result of their demise. http://www.arteconomics.com/publications/death-effect.html

In a question and answer piece on the site artbusiness.com, the death effect is explored further Here is an excerpt:

Q: I bought six paintings from a local artist over a twenty year period during his career. He's pretty old now and I'm thinking about selling. Should I wait until after he dies? Will that make any difference pricewise?

In some instances, an artist's prices can actually drop on the occasion of his death. For example, an executor or family may mismanage the estate by dumping all the art on the market at once and temporarily depress prices. Another reason for a decline in prices is when collectors patronize an artist more for his personality, media image, flamboyance, social contacts, or sales skills than for the quality of his art. With the artist's number one promoter gone (namely himself), art values fall flat.

for the full piece, visit http://www.artbusiness.com/postprice.html

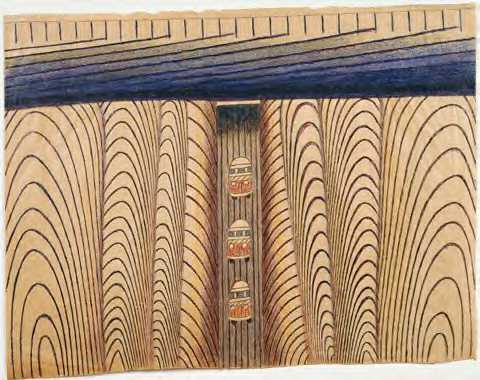

Untitled, Martin Ramirez, Auburn, California, c. 1954

But do not despair, gentle reader. The post mortem bump can occur for even the most humble of artists. Here in an excerpt from CBS News, is the story of Martin Ramirez:

Ramirez was 30 when he left his small ranch in Mexico America California

Few outsiders ever saw Ramirez, who would spend the rest of his life in mental hospitals. For much of the 32 years he spent in mental institutions, Ramirez lived in silence.

As a student in the 1950s, painter Wayne Thiebaud was allowed to visit him.

"I was surprised because they told us that he was mute and didn't speak," he said. "This would be the kind of thing he'd pull out of his shirt. And it had a picture that I recognized of what I thought was a shoe. And, I asked him, 'Hey, Zapata?' He said - and the first words he spoke all day was - 'Si.' So, I said, 'Do you have other ones like this? Mismo ese?' And, he says, 'Si.'"

For Thiebaud, today a world-renowned artist, Ramirez's work was a revelation.

"What you look for, I think, if you're interested in painting and drawing, are those things which captivate you in some way, which sort of knock you off your feet for a minute," he said. "You don't quite know what's going on. And along that line, his work has this very riveting kind of attention."

Intense and obsessive, Ramirez returned again and again to the same themes. Gun-toting caballeros - he drew more than 80 of them. Trains emerging from tunnels.

"He loved transportation, whether it was a horse, or a truck, or a car or a train. He was rather enamored of that," Thiebaud said.

Self-taught, he used traditional tools like crayons, but in his own way.

"He'd melt down the crayon into wax and he'd apply the wax with a wooden matchstick," Anderson

The conditions were anything but ideal for an artist.

"It was not uncommon to have a fight on the ward, that we had to break up, between these more violent patients. So I think Martin was fearful," said James Durfee who supervised the tuberculosis ward at Dewitt State Hospital

Ramirez sought refuge by going under tables. Durfee crouched under a table to demonstrate Ramirez's technique. "I saw him do this for hours," Durfee said.

"He used a tongue blade for a ruler. We gave him many rulers. But he used a tongue depressor for a ruler. And a wooden matchstick."

How many drawings Ramirez did isn't really clear. In the early years, the hospital sent many of his works back to his family in Mexico

Ramirez's work might not have survived at all if it hadn't been for a professor at Sacramento State College, Tarmo Pasto, who was researching mental illness and creativity. Thiebaud was Pasto

"And he's I think the first one to take him seriously," Thiebaud said.

On visits to Dewitt, Pasto

"I think he had no idea he was making art," Thiebaud said. "He just wanted to make these powerful images, which for him was a little kind of world. And those little worlds in painting and drawing are kind of human miracles."

"This piece of a train and a tunnel is built up from lots of different kinds of paper - candy wrapper bow, greeting card, found paper and pages from a book. The title of that book - you're just gonna die - is 'The Man Who Wouldn't Talk,'" Anderson

Drawing by Martin Ramirez

But here the story takes a miraculous turn.

After the Ramirez show opened in New York

"I was a little skeptical, as she likes to remind me now," Anderson

But the woman, a relative of Max Duneivitz, who'd worked at Dewitt Hospital

"Kept in a pile in a garage in Northern California , on top of a refrigerator, sandwiched between the refrigerator and a sleeping bag," Anderson

When Anderson California

"Well, by the time I got to the last one, I think I started crying," Anderson

With one discovery, the 300 known works of Martin Ramirez had grown to 440. The new pictures were all drawn in the last years of his life, and some are epic in scale.

There are more of the familiar cowboys, but now blasting trumpets.

"I mean you can hear it," Anderson

The American Folk Art Museum

1 comment:

What a spellbinding and very moving story. What an astonishing artist - what a captivating vision he had.

I've just done a search on google images and found lots of his work.

Thank you, Patrick. And not for the first time!

Post a Comment